A young, proud Singaporean takes up arms against misconceptions about our beloved Singlish

Reprinted post by Grace Teng, with foreword by Frank Young

FOREWORD

Singlish is functional, entertaining and, more importantly, helps to unite our heterogeneous culture. For better or worse, it is our very own.

Sadly, the notion of language is often misunderstood. A language, such as English, is not static. It is dynamic, like a moving river, ever shifting, influenced by time, geography, technology and contact with other cultures, as Grace Teng argues in her post [which you will see, right].

Language is a tool, which its users shape over time. Like many other cultures and subcultures around the world, Singaporeans have naturally done so with the English language over the years.

Is Singlish a replacement for World English that we learn in school or use in business? Absolutely not. Just as a person would not wear slippers and shorts to a business meeting, you wouldn’t (or shouldn’t) use Singlish either. They are simply different tools for different purposes.

A recent question posted on Quora.com (a popular website for posing questions and crowd-sourcing answers) implied that there must be something wrong with Singaporeans because we don’t speak “proper English”.

One highly-favoured and insightful response came from Grace Teng. We reprint her views here in their entirety, with her permission.

Question:

“Why don’t Singaporeans try to speak proper English?”

Grace’s response:

Oh wow. You’re spoiling for a fight.

Firstly, Singlish is not bad English. It has its own phonology, its own syntax, and its own grammar. It is possible to speak bad Singlish, just as it is possible to speak bad English. Singlish is a creole, and while there isn’t a lot of agreement as to what defines a creole, many creole languages suffer from perception problems; they’re seen as “corrupted” forms of a “proper” language.

Many creoles exist on a dialect continuum. On one end is the acrolectal form, the “proper” form of the base language (in this case it’s English), and on the other end is the basilectal form (in this case it’s Singlish). Even the terms “acrolectal” and “basilectal” are loaded terms but I’ll just use them anyway.

I should say that it’s not just creoles that form parts of a dialect continuum. Pretty much any regional accent will also exist on a continuum. In the UK, for example, the acrolect is Received Pronunciation / Queen’s English, and the basilect could be Scouse, Geordie, Cockney, Brummie… If you go to Liverpool, Newcastle, East London or Birmingham and tell them they’re speaking bad English, you’re not going to have a good time.

Besides, the huge diversity of languages that we have today came from somewhere. Once upon a time, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, French, Catalan, Galician, Occitan, Romanian, etc. were “bad” Latin.

I’m going to make a bold, somewhat tenuous (but I think correct) claim here – Singlish shows many traits of natural language, it is consistently spoken the same way by a large group of what are, in effect, native speakers of Singlish, so we should consider it a language in its own right. (It’s still a creole on one end of a continuum, but for the purposes of this argument…)

Singlish is under-researched, except in sociolinguistics, but here are some things about Singlish phonology and grammar that I bet you never thought about:

Singlish is syllable-timed, unlike American and British English, which are stress-timed. This means that in Singlish, each syllable takes the same amount of time, while in American and British English, the interval between two stressed syllables takes the same amount of time.

Vowels are usually fully articulated. In American and British English, unstressed vowels tend to be pronounced as schwa or as a lax high front vowel (the “I” in “bitter”). Not so in Singlish. “To”, for example, will be pronounced /tu/ regardless of stress.

Consonant clusters are reduced and a lot of phonemes get elided, especially in running speech. How does a Singlish speaker know that “liddat” means “like that” and “dowan” means “don’t want”? Those are just the canonical examples.

Listen to a Singaporean the next time he says “I don’t understand”, and see what you actually hear, not just what you think you hear. Curiously, in Singlish, word-initial consonant clusters are never reduced, yet reduction can happen across a word boundary.

A quirk I recently noticed: th-stopping and th-fronting happen allophonically. In non-technical terms: when “th” appears at the start of a word or after a consonant cluster, it is realised as /t/ or /d/, when it appears at the end of a syllable or between vowels it is realised as /f/ or /v/.

Topic prominent syntax – the most important part of a sentence goes to the beginning, regardless of part of speech. “The camera must bring hor” (noun – object), “Blur lah him” (adjective), “Faster go if not no more seats” (adverb), all acceptable constructions in Singlish that are not acceptable in English.

The set of acceptable syntactical constructions in Singlish is a superset of that of English. And if you doubt that this is even syntax, think about this: Why can’t we say “lah cannot make it”?

Productive morphology – Singlish allows you to apply English morphology to any lexical item, regardless of origin. “Nuah” can become “nuahed” or “nuahing”, “kope” can become “koped” or “koping”, same with “chope”. The word “agaration”, from the verb “agak” and the derivational suffix “-ation”. Nouns, too: kopis, kuehs, goondus…

This is just the tip of the iceberg. Trust me, I could go on. Nobody sat in a room and said, we shall all speak Singlish this way; let’s write a grammar of Singlish. There is a wrong way to speak Singlish, but at least two generations of Singaporeans have now learned to speak a language that is remarkably consistent in its own phonology and grammar across speakers, when considered separately from English.

I also want to make a distinction here between speaking Singlish and speaking English with a Singaporean accent. To an English speaker from a different part of the world, the latter sounds like English with a different accent, while Singlish often sounds like a completely different language.

Now to the other part of your question: Why don’t Singaporeans speak English more often instead of Singlish?

Because, like it or not, Singlish, not English, is what we grow up speaking. It’s what we hear in our homes growing up, it’s what we hear when we go out, it’s what we hear in schools and informally in the workplace, and it’s what we become comfortable with from a young age.

We think in it, its lexis and syntax are what come most naturally to us, it becomes the default medium for expression. I know my argument is tautological, but since I’ve spent all this time arguing that Singlish has many features of a naturally acquired first language (as opposed to features of an imperfectly acquired second language), what I’m really saying is, you wouldn’t ask a Frenchman why he prefers to speak French over other languages, would you?

Let’s consider a different case of diglossia (two different but closely related languages coexisting): Do you ask why Cantonese speakers in Guangdong or Shanghainese speakers in Shanghai don’t speak “real Mandarin Chinese”? They do speak it when they have to, they just prefer Cantonese, Shanghainese, etc. for daily communication.

Same goes for Catalan/Galician/Aranese/Asturian/etc. and Spanish, same goes for Bairisch/Schwäbisch/etc. and German, and same goes for many, many diglossia situations around the world. Just because Singlish is a creole doesn’t mean it’s any different from the above cases. (In this respect, the Bairisch-German comparison is probably the most accurate.)

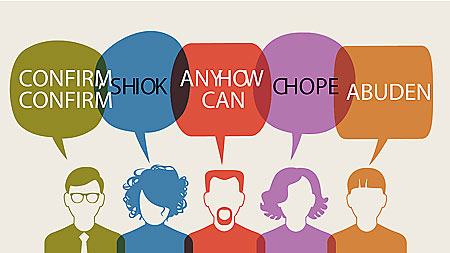

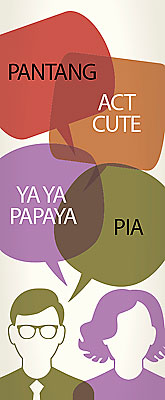

Besides being a first language of most Singaporeans, or perhaps because of it, Singlish also has features that make it feel unique to a Singaporean – the staccato quality (due to our tendency to insert a glottal stop before a word-initial vowel), its syntactical efficiency, its varied lexis drawn from many different languages – all Singlish speakers know what “shiok” means and yet not one person can give an accurate definition of it to a non-speaker.

Some things simply do not feel the same expressed in English: Can you find a way to say, “Why you so like that?” that conveys the same measure of annoyance and curtness?

Heck, why do we even have any linguistic diversity in the world, why don’t we just make everyone speak English? It’s because each language has its own fluidity, its own quirks, its own peculiar expressions that are beautiful in and of themselves, and speakers of different languages want to preserve that.

I will admit Singlish is a “problem” when the speaker isn’t aware of where he or she falls on the basilectal-acrolectal continuum. It is a problem when Singaporeans think they’re speaking English when they’re not, and I have also encountered the reverse (when Singaporeans think they’re speaking Singlish when they’re only speaking English with a Singaporean accent – yes, it happens to Singaporeans abroad).

But if we continue to pretend that Singlish doesn’t exist as a language in its own right, we’ll never begin to be able to sort out what makes Singlish Singlish, what’s bad English, and what is actually good English.

Grace Teng

We would like to hear your thoughts. E-mail us at [email protected] or [email protected].

Visit pelicularities.net for more about Grace Teng.

ADVERTISEMENTS